Faces Behind the Screen: Leon

RESOURCES

< < Return to all “Faces Behind the Screen” stories

Leon is a tour guide at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

He leads visitors, deaf and hearing alike, around the MFA’s beautiful campus while giving historical and cultural context to the museum’s featured pieces in American sign language (ASL).

A tenured guide at the MFA, Leon has a deep appreciation for not only its vast and legendary art collection but also its commitment to making that art accessible to all visitors through its multimedia tours and technology like assistive listening devices.

Leon is also well-spoken and passionate about education and equality in learning and job opportunities for deaf children. As someone who himself fought discrimination, stigma, and societal expectations to get to where he is today, he knows a thing or two about the importance of that topic.

The text in this story is transcribed from the voice of Leon’s ASL interpreter:

Do you identify as d/Deaf or hard of hearing?

-

- I would call myself capital D, Deaf.

I was born and raised in a more oral method of instruction for the deaf where they teach you to speak and understand lip-reading. My father didn’t actually permit me to sign. And that was the 1970s or so. My mom did sign a little bit, mainly just home signs (invented gestures), but my father required me to speak when he was around.

And then I went to Gallaudet University for a really short time and I was very happy there. Gallaudet University is very Deaf-friendly, capital D Deaf. Deaf families go there.

So, I felt a little bit left out, actually, because I entered identifying as, or thinking of myself as hard of hearing, not culturally Deaf. I wasn’t part of that larger community of culturally Deaf people that made up the majority of the campus. Because, I had grown up in this world that was more speech and reading lips. My dad had required that of me. So, that experience really impacted me and my identity.

So, I decided after my time in university to call myself capital D, Deaf. Before Gallaudet, maybe when I was 23 or so, I had always called myself hard of hearing because that’s what I was told was my identity. People said, well, you’re hard of hearing because you can speak.

It was a sign of the times, the ’70s, ’80s… They really tried to get deaf people to fit into a hearing world and a hearing context, rather than trying to make accommodations for deaf people within the Deaf context.

I was always told that deaf people were oppressed, or had more negative stigmas attached. That they didn’t have jobs. So, my family always told me I was hard of hearing. So, I grew up believing that and speaking, reading lips.

But after Gallaudet University, that’s when I discovered my Deaf identity.

How did you find yourself leading art tours here at the MFA?

-

- One day, here in Boston at the MFA one of my friends said, they have an ASL tour here. And I said, oh, an ASL tour at the museum? Okay, fine, I’ll just go for it.

And they were talking about cubism. I sat on the back of the tour because I knew everything that the person was saying.

And so after a while, the tour guide said, why are you just on your phone? Is everything okay? I said, oh, yeah, it’s fine. She said, are you not interested in the topic? And I said, oh, I love it. I’m just very familiar with it. I know all of the information. She said, oh, really? Do you know this and this and this and this?

And I knew all of the art history. And she said, wow, you should just become a tour guide for these ASL tours. And it was the first time someone had given me that idea. So, she planted the seed.

So, what is your background in art?

-

- It’s mostly because of my mother. I was born in California. And at that time, in that area, we were in bungalow buildings. So many of the homes were those bungalow-style houses, Queen Anne’s style houses, or stick style houses.

I was just always researching as a young kid, reading books, and all the time there was art involved. There was always art in my life.

And I remember driving and pointing out the different types of architecture, and I always said the years in which they were built. And my mom said, wow, you know all the architectural styles. And I would say, oh, this year, this time period had this style of house.

So, my mom said, “you should definitely become a history major in school.” And I said, “but, I don’t really want that.” I always felt like, I can’t hear. How am I going to get a job in a museum? How am I going to talk to the hearing people? The mentality of the ’80s was that I couldn’t find a job as a deaf person, that hearing people would be more competitive in the museum jobs than I would be.

I always said, oh, that’s a hearing job. I can’t. I need to find a more Deaf job within a Deaf school or work somewhere within the Deaf community. My mom always told me I would find a hearing job, somewhere I could fit in. But I always told her no, that’s a hearing job, I can’t.

And I studied art through college, I studied art history, took a few courses. And I just loved, as a hobby, reading art history books, especially European history. I just fell in love with it.

I just told my mom, actually, recently — I said, you’re right. I should have been an art history major when I was young. My mom was right. Mom’s are usually right.

How do you feel about job opportunities for deaf children growing up in today’s world?

-

- I don’t feel that it’s the same nowadays. I would say, I think now the younger generation knows that they have more opportunities, that they can do these things.

-

- Here in Boston, the school districts, for example, have Deaf teachers. They have Deaf school psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors… Having those adult role models helps deaf children to think, wow, I could succeed. I could do this. I could do this as work, as my career. Art museums, departments of mental health, counseling… there are lots of deaf adults working in those careers. So I’m sure nowadays, the kids see the opportunities that they have and they say, wow, I can be like them.

-

- Schoolteachers these days are better at saying, oh, there’s this deaf person that does this and this and this — at introducing those deaf role models. And there’s social media, seeing the successes of others,

Switched at Birth

- , for example, that TV show. Kids watch that all the time. And they see the success of these [deaf] actors. So, there’s a lot more realization of the opportunities compared to back then.

Do you feel like there’s more access today?

-

- Definitely more. Way more because negative stigmas are being removed now.

- And in the past, in my time, my schoolteachers were all hearing, and they’d sign in English, which is much different than American Sign Language as a visually and grammatically structured language.

Can you explain the difference between ASL and “signing English?”

-

- Signing English, or Signed Exact English, is when a hearing person has decided that you as a deaf person have to learn how to write and read English.

-

- For example, in English, you say, “you and I are going to the store.” That’s how it’s signed in Exact English. In ASL, you would sign “store we go.” ASL has its own grammatical structure, and it uses physical space to set up the “store” — I set it up in space with my hands and my body. Then persons, places, names, and verb follow.

-

- So, if you’re taking a French class, and you’re sitting there all day long, and you’re learning French, you might be struggling with it. But if the teacher is teaching you the French language while speaking English and working off the basis of what you already know, using that to explain the grammatical structure of French and the different terms used, then it would be easier for you.

-

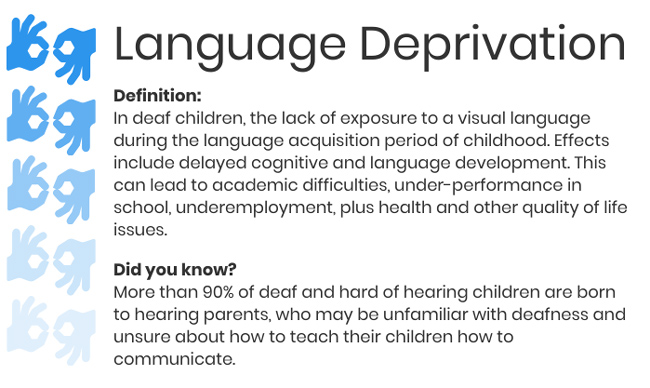

- I didn’t get that growing up. It’s called Language Deprivation when deaf children experience that.

Language Deprivation is the lack of a language’s exposure to a child during the language acquisition period. This leads to the child struggling to understand complex intelligential stimuli. Not only that, but they are often more at risk for living an unhealthy lifestyle, being under-educated, and experiencing underemployment.

It’s very difficult. There’s a lot of shame involved. There’s a lot of repression involved. And there’s a lot of attitude that the deaf child can’t do everything because they are deaf.

But now, since Nyle DiMarco has been in Dancing with the Stars and won, there’s an attitude of, “If he can do it, I can do it.” And that’s really a more prevalent attitude nowadays. And today, of course, more and more Deaf teachers are teaching English literacy skills using ASL, using grammatically correct ASL.

Can you give a piece of advice to hearing people who want to understand more about the deaf community?

-

- I would say, go for it. Meet the Deaf people. Encounter them. Say hi, how are you? Learn from them. Write back and forth, whatever you can do.

Say, it’s nice to meet you. Find something in common ground with them. Saying, “hey, I want to learn sign language” is a great starter. And then the deaf person can give some tips and places to learn that.

Meet any deaf person in your book club, any social club, anything like that. Come up, say hello. Say wow, I like sign language. It’s beautiful.

Start that conversation. Start from there. And maybe you’ll have a great friend the rest of your life! You never know. But don’t be afraid to get out there and meet people. And again, take a class, an ASL class at your local community college, or get into Deaf studies or an interpreting program. Learn.

We would like to extend a huge thank you to the Museum of Fine Arts for hosting us and giving us the opportunity to conduct this interview.

To join a guided tour at the MFA, refer to this schedule.

Faces Behind the Screen is a storytelling project focusing on members of the Deaf and hard of hearing community.

![It was a sign of the times, the 70s, 80s... They really tried to get deaf people to fit into a hearing world and a hearing context, rather than trying to make accommodations for deaf people within that [Deaf] context.](https://www.3playmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/leon-quote-3.jpg)