Rules of Thumb: Copyright Made Simple for Classroom Instructors

Updated: February 23, 2021

Professors and classroom instructors, has this ever happened to you?

You find a great image, video, PDF, or another form of digital media and you’d love to share it with your class… but you don’t know if you have permission to do so.

Or maybe you want to add captions to a third-party video file for accessibility purposes.

How certain are you that the media you share, and the way you share it in the classroom is legal and fair to the author?

Navigating copyright law isn’t actually as hard as it seems. If you’re armed with a basic knowledge of how copyright laws work, it’s easy to determine which media is acceptable to share and when.

If you’ve been teaching for a while, you probably have a pretty good grasp on how to responsibly handle most forms of media. But just to be sure, we’ve put this post together as a short guide to sharing content properly and, ultimately, avoiding any risk of accidental copyright infringement.

We hosted a crash-course in classroom copyright rules to help instructors everywhere stay on the right side of US copyright law.

Dr. Tom Tobin, Coordinator of Learning Technologies at Northeastern Illinois University, introduced a few short-hand rules of thumb, mnemonic devices, and basic concepts to help instructors avoid risk when copying and sharing learning materials.

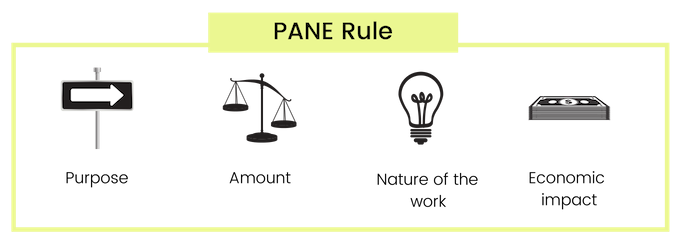

The ‘PANE’ Rule

Fair-use is the first thing you need to understand if you commonly share media with other people in your line of work.

Essentially, fair-use is a means to defend yourself if someone takes you to court for a copyright violation.

Any time you make a copy of something, you need to make sure the manner in which you share it is fair to the content’s creator. The PANE acronym is an easy-to-remember tool, drawn from the language in the Copyright Act of 1976, which you can use to ensure you are sharing content fairly:

- Purpose: You are using content for criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship or research.

- Amount: You are using as much as you need and not more (meaning it is hard to prove you’re copying the whole thing).

- Nature of the Work: You aren’t copying too much information from creative works (factual works are more lenient) and it is not used repeatedly.

- Economic Impact: Your use of the content or material will not deprive the creator or author or revenue or profit.

Let’s unpack PANE a little further…

Purpose

Generally speaking, North American copyright law allows classroom instructors to copy and share limited, relevant, third-party material in the classroom environment as they see fit.

That being said, Tom has one important thing to add about for-profit institutions:

“If you’re working at a for-profit institution, your purpose is almost always commercial. So be careful if you are working at a for-profit college or university. Even if you’re creating materials for teaching, the fact that your institution is for-profit means that you are at best making a neutral case under purpose.”

Amount

All this section means is that you should be sensitive to using smaller amounts of the content. Don’t copy more than you need to copy, or share more than you need to share.

Nature of the Work

Pay attention to the type of content you share, how much you share it, and whether it is necessary to share it.

For instance, a judge will likely find it very hard to understand and approve of your decision to allow on-demand streaming of the entire Lord of the Rings Trilogy in your Microeconomics course every semester through your online learning platform. Creative works, when used in such a setting, should only be used as much as the situation requires — use your own judgment.

However, if you want to distribute paper copies of a relevant Wall Street Journal article in a business class, your argument for fair-use becomes much stronger.

Economic Impact

This is the first thing judges look at in copyright lawsuits. You should not share and copy material in a way that deprives the author or revenue or profit. So, if you want to share one or two pages from a textbook with your class, that’s fine. But if you copy the whole 400-page textbook worth $300, and share it with your class as a PDF file for free, you’re looking at a very difficult defense for fair-use.

The Creative Commons Licensing Scheme

Copyright is the standard set of rules for copying and sharing, but licenses can legally deviate from that law by either adding or subtracting restrictions on the use of the media in question.

The Creative Commons is a universal set of licenses utilized across the internet that authors and creators can use to allow limited kinds of uses to the public domain while preserving the rest of their copyright.

If you encounter media that you really want to use but aren’t sure what licenses are on it, check for any of the following Creative Common allowances:

- Attribution: Copy, distribute, display, perform, and make derivatives only if you give the author credit.

- Noncommercial: Copy, distribute, display, perform, and make derivatives only for non-commercial purposes.

- No Derivative Works: Copy, distribute, display, and perform only verbatim copies of the work.

- Share-Alike: Distribute derivative works only under a license identical to the one governing the original.

The Noncommercial license restricts the use by for-profit institutions.

TEACH Act and DCMA in Higher Education

The TEACH Act (Technology, Education and Copyright Harmonization) and

the DMCA (Digital Millennium Copyright Act) are laws that were passed in the late 1990s and early 2000s to try to close loopholes in the 1976 Copyright Act.

These laws typically pertain to digital media since the Copyright Act was passed in 1976 before the internet even existed. Thanks to the internet, authors and content creators have a new medium to share their work with a larger audience.

The DMCA and TEACH Act was designed to close loopholes in the copyright law so that you can make copies under fair-use without running into some of the broadcasting restrictions that the FCC has put in place.

This is actually one of the reasons why you can show a whole film in your physical classroom by pressing play on your player and showing it on a television screen. However, you can’t copy that whole film and put it into your online course environment and let your online students see it, because that’s considered broadcast.

Tom Tobin encourages instructors to take a look at the University of Texas at Austin’s libraries for a quick guide to the TEACH Act.

Captioning Videos You Don’t Own

There may be instances you want to show a YouTube video to your class, however, there are no captions available for students who may need them as an accommodation.

For anybody who uploads a video to YouTube, they now have a lot of options for adding their own captions. It’s never a terrible idea to drop the person a note who created the video and say, “Hey, why don’t you think about adding captions?” YouTube makes it very easy to do so now.

But let’s assume you’re a professor who has decided to use a YouTube video, and the question you have is whether you can legally add captions.

So, is adding closed captions to an existing YouTube video going to be a copyright law problem?

In general, unless you are doing something like selling the captions, using them for some purpose other than education, or making them widely available potentially for people to sell, then you’re still in good shape under fair-use. The copyright problem there is pretty nominal, but it’s also worth considering the risk there.

There are often ways to make the captions available only to the folks in the class. In that case, you’ve got to ask yourself, who is going to track down the fact that you captioned the video for your class and get so mad about that they’re going to file a lawsuit against you?

Now, that doesn’t mean that nobody will ever do that, but in that case, you’ve got a very, very good argument that what you’re doing is fair-use and there’s a very low likelihood that anyone is going to care about it.

The person who’s going to care the most about the video not being captioned is the student in your class who is paying the university a lot of money and who is entitled under federal law to get access to the captions.

There are common misconceptions about restrictions on the length of the video you can caption under fair-use. When we’re talking about captioning, the whole reason you’re doing it is to make the video accessible to a student with disabilities. So would you be able to successfully do that if you captioned 30 seconds of a five-minute video you’re showing? Of course not. That’s not equal access for that student. The reason that you’re trying to caption it is to give the student access to the video.

Whatever you arrive at for your students in general, your students with disabilities ought to get access to the same amount. So if that means you’ve got to caption an entire video because you provided access to that entire video to students without disabilities, then that’s what you’ve got to do. If it’s OK to show five minutes of the video to the rest of the class, it’s OK to caption five minutes of the video for your students with disabilities.

You’ve got to be careful about hosting videos online that you don’t own in general. But if you’re going to make them available to your students, it adds a pretty limited risk to make them accessible to all of your students, including your students with disabilities.

Foreign Copyright Law

If your university has some sort of presence or is teaching students in a foreign country in a way that it might be subject to lawsuits there, you might be at risk. Countries across the world have very different copyright laws than the United States and not every country has fair use.

It really depends on what countries you’re talking about and what the classroom situation is. In other words, are you teaching to students in that country? In that case, it may be worth getting familiar with the copyright laws in that country.

Translations and Copyright Law

A lot of folks will say, OK, I’m adding closed captions, and by the way, while I’m at it, why don’t I convert the video so that it has Spanish subtitles if I’ve got students that speak Spanish as a first language? Or why don’t I convert the video to French, or to Chinese — and there may be lots of good reasons to do that.

That gets a little bit trickier as far as copyright law goes. In particular, copyright owners tend to get a little bit more nervous about the translations because a lot of the strategies around selling videos involve selling them in other countries a couple of weeks later or a couple of months later with the foreign language subtitles.

So if you are captioning a video and translating it into another language, you have to say, OK, we’re getting out of a strictly accessibility-oriented purpose and we’re looking at foreign language translation. And then the question gets a little more complicated and you have to ask yourself, are we doing this to a video that we think the copyright holder is going to get upset about? Is this a mainstream movie or a TV show? Is this something that we’ve got to be worried about?

On the other hand, it might be a video that a professor at a foreign institution has created who might be totally fine with you doing that. In general, when foreign countries get into the mix, you’ve got to be a little bit more careful.

Licenses and Permissions

Licenses cannot restrict your fair-use rights. However, licenses and permission trump the law.

If a license says you may only make a copy of this and share it with people on Wednesdays in months that have an R in them when there’s a full moon, you have to abide by that. Now you might not make the copy if the restrictions were that crazy, but licenses are agreements between two people so that they don’t have to rely on the broader law. Licenses are almost always more restrictive than the fair-use rights that you have.

Now, if you wanted to, say, download a copy of something from your library databases and keep that copy on your hard drive, you actually do have a good fair-use case for doing that, because it’s for the purpose of research or scholarship. It’s when you start making that copy available to others and sharing it that you have to really take a look at what your licenses tell you. The right people on your campus who can tell you what those licenses allow you to do are your librarians.

Materials Created at Universities

If you work for a company, everything you create for that company on company time and using company resources belongs to the company. They own it. They have the copyright to your work. That’s called work for hire.

In higher education, however, there is a longstanding tradition of allowing faculty members to own the copyright for the content and materials that they create. That’s why many colleges and universities have policies and contractual agreements in place that state who owns what.

Now if you’re creating content on your own time and with your own equipment, you definitely own that.

For legal advice on material created at universities, Tom encourages professors to contact the legal counsel at their institution to get more clarity.

Things Not Protected by Copyright

Finally, here are some things not protected by copyright that you can feel free to copy and share at will!

- Hyperlinking and streaming video via embed/share code

- Any works published by the federal government

- Any works that have been around 70+ years after the author has died

- Any works which the creator has intentionally decided to release the rights to the public

Note: Dr. Tom Tobin is not a lawyer and this post does not constitute legal advice.

Still not sure you’re sharing fairly? Check out the full webinar, Copyright Made Simple for Digital Educators:

This post was originally published on November 23, 2016 by Patrick Loftus and has since been updated.

Further Reading

Subscribe to the Blog Digest

Sign up to receive our blog digest and other information on this topic. You can unsubscribe anytime.

By subscribing you agree to our privacy policy.