Faces Behind the Screen: Joshua Pearson

Quick Links

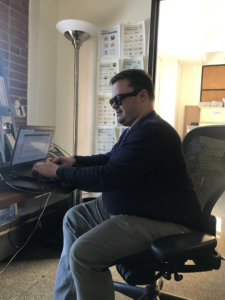

Joshua Pearson is an Assistive Technology Specialist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He started his career at UMass a little over 9 years ago as a student studying communications, and eventually went on to become an employee of the university. Follow Josh’s personal Twitter account for all things on disability advocacy.

In his spare time, Josh enjoys writing, podcasting, documentaries, and music. He is also a traveling folk musician. Check out his early albums!

You can find Josh championing for accessibility by day, or performing at local bars and venues around Western Massachusetts by night. Keep a lookout for a new album that is currently in the works and set to come out in the Spring of 2020 on iTunes, Spotify, and all major music streaming platforms.

To keep up with the work from UMass’ Assistive Technology Center, you can follow them on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Part One

After studying at the University of Massachusetts Amherst I had a 4-5-month unemployment gap. I went out into the world and encountered a lot of ableism while looking for work. I then realized that my talents could best be served in giving back to the UMass community and making sure that people are afforded the same opportunities to access technology in education

as I was.

I feel passionate about the community work that I do here. It allows me to contribute to the conversation on campus around disability justice/culture and disability as a social and cultural identity, as well as serving the people outside of what we typically think we’d serve in the disability services population. There are a lot of people with invisible disabilities who, for reasons largely of stigma, don’t feel like they can disclose or adopt that as an identity. So, my goal is to make sure that as many people as possible have access to this technology and know-how to effectively implement it into their lives. This gives people with disabilities agency and power over their rights, lives, and most importantly their own advocacy, and provides an equal playing field. When we give people with disabilities access to the tools they need through an inclusive environment, we set them up for success, champion their independence, and acknowledge their innovations and contributions to society.

As an Assistive Technology Specialist, I evaluate the technology that people use. I figure out what hardware or software is best going to fit a faculty/staff member or student’s life so that they’re able to do their job, access their classwork, and most importantly live an independent life on and off-campus. That includes every kind of disability – physical, cognitive, speech, hearing, vision, and psychological.

I train people on the tools and then educate the campus community on assistive technology. I lead presentations and group workshops in order to get the word out about different types of tools.

There’s also an innovative component to my work. I look at where the gaps are in our society that aren’t met by current assistive technologies and how we, as a university, can use that to our advantage in order to build new technologies.

I work with departments across campus and organizations beyond the university. There’s definitely that sense of community outreach and this idea that technology impact’s everybody’s life. It impacts both able-bodied and disabled people. An accessible world is a world that’s inclusive for everybody. Oftentimes, when accessibility and assistive technology are implemented into society, it typically benefits everyone. And anybody can join the disability community at any time during their life, so setting them up with tools can combat fear and discomfort somebody new to this identity might feel. I help people reach their full potential with these tools, many of which are free and built right into the operating systems of computers and mobile devices.

It can get exhausting for a person with disabilities to constantly advocate and push for inclusion in every single aspect of our society and to constantly be aware of the gaps where the world was clearly designed with able-bodied people in mind. It’s the same type of burnout that people who are dealing with constant racism or sexism or issues around identity face. So, these technologies, if implemented in the right way, can mitigate a lot of that burnout because the culture by rote is accessible rather than having to put that ownership on the individual person to always do the extra work of advocating for their accommodations and educating on why they are necessary in the first place.

People are just waking up to the fact that a quarter of the population has some form of disability and have the same right to independence and freedom. It’s not that people are being malicious or ignoring this, it’s that people historically have been too tired to talk about this – myself included, and the able-bodied world doesn’t really understand the experiences of being disabled except to view it with fear or pity, or to hail somebody living successfully with a disability as a hero and amazing for living their life utilizing adaptive tools.

Disability is often seen through the lens of overcoming adversity. And living in that, day in and day out, trying to build a better educated more inclusive world, while at the same time living one’s life and overcoming ableist obstacles created by a lack of inclusivity and accessibility can weigh on a person. That’s why some activists drop out, why the college dropout rate for students with disabilities is so high. We have to figure out what disability means to us while also living it every day. It’s taken me a long time to get to the point where I feel like I know what my message is. I know what I want to say. I had to go through that identity shift of figuring out what disability meant to me and if I wanted to be an ambassador because it’s constant – there is no off switch. That’s why I love art, radio, and music so much. It’s a vehicle for me to connect with people independent of the disability advocacy work that takes up so much of my life – because it is my life.

That echoes a lot of people’s experiences too because you’re just trying to get through the day, and that can be exhausting enough depending on what type of disability you have and how much ableism you face on a daily basis.

Typically, in a higher education setting, a disability is looked at from a medical model, which suggests disabilities and people who have them need to be “fixed”, and that responsibility for individual advocacy and accommodations often falls on the person living with the disability. It’s a compliance-based model of the federal standards that have to be met according to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) as well as the technical standards that have to be met according to all the various laws that govern accessibility and assistive technology.

Many times, they’re not looking at the human side of things, which is the social model of disability. This is the idea that disability is not a bad thing or a detriment to a person if we can build the world to be inclusive. It shifts the focus from, again, placing this on a person’s shoulders to really putting the responsibility on society’s shoulders to fully embrace disability and alter the built physical and digital environments to include every single person. This way of viewing disability, and providing societal accommodations, fixes the world for everybody instead of providing one set of accommodations for one single person.

Universities are slowly changing how they view disabilities. Activists are calling for disability studies programs and disability cultural centers. This is putting universities up in line with other institutions across the country that have tackled disability from the mindset of true inclusion.

So that’s how I approach my work – from the sense of true inclusivity. I think about the tools that we can give people and how we frame disability as a society so that it’s not just on individuals getting accommodations and always having to self-advocate. However, what I do is a very small part of that. In my private life, I’m a disability rights activist. I’m very aware of the disability justice movement and the push to take the negative stigma away.

Usually, nine times out of ten, ableism is not meant as maliciousness. It’s just that our society hasn’t been properly educated, and we haven’t had the large cultural and political conversations around disability as an identity as we have with other identities. Part of that is because up until 30-40 years ago, we were institutionalized instead of being allowed to live our own independent lives. We’ve had to fight very hard for our civil rights – for the right to education and equal employment and social standing. It’s a battle that’s still going on and it’s not talked about with the same frequency as other social-political identities.

We need to get to a place in our society where we’re having these open, frank, and honest discussions about disability. It’s about normalizing the existence of assistive technology; normalizing the fact that there are going to be people who talk to their computers or use manual wheelchairs in public, and normalizing the existence of a quarter of our population and ending the stigma around disability disclosure. With the right tools and an inclusive environment that truly values people, anyone has the chance to succeed. We just need to focus on the positivity of disability, the innovations disabled people bring to the world, and stop telling people they are broken or will always have to make up for a perceived flaw.

From an educational stance, we have to figure out how to get people to understand that people with disabilities are just as capable as an able-bodied person if we’re given a chance to be capable.

I identify as a blind man. I was born 4 and a half months premature and weighed 1 pound 8 ounces. Three weeks after birth, my lungs collapsed six times because they weren’t fully developed. The doctors had me on 100% oxygen to keep me going. The oxygen caused the blood vessels in my eyes to swell and burst, detaching my retinas. I’ve been blind since then. It was either blindness or death. Happily, I will take the blindness.

I’ve never believed that there are limits to what I can do based on the fact my eyes don’t physically function. The limits out there come from the attitudes society has around blindness. My own personal way of tackling that is to put blindness first. It’s true, I am a person who is blind, but blindness is a huge part of my identity too. It’s how I interact with the world. It’s given me a unique viewpoint on humanity and life. So I identify as a blind person. Ramblin Blind Josh Pearson is my stage name for my music, because I want to put people at ease with disability and for them to know I’m completely comfortable with me being a disabled person; systematic ableism is the thing I’m uncomfortable with.

At first, I started working in the blind community teaching specifically blindness-related technology. Now that I’ve been working in assistive technology for a while, I’ve advanced beyond that and look at the wider disability community and its place in the world. The work I do encompasses blindness and every other disability under the sun, and I’m trying to make sure that we’re giving people the tools needed to succeed.

Part Two

I was really fortunate to have been raised by parents who never believed there were any limits to my abilities. I grew up on a farm and was expected to do all of the farm chores, including caring for our plethora of animals, toting wood and shoveling snow.

Growing up, I never believed my blindness to be a hindrance because it was just a fact of life for me. The only times it’s been difficult has largely been around facing society’s attitudes towards it. Ableism is not something that is discussed much in society, and it is something that has not received widespread conversation in the blindness community. I was 25 before I knew the word, but have long been able to identify ableist attitudes of people who question my capabilities to function in the world. What they fail to understand is that my blindness does not stop me from living my life independently; what gives me pause is constant exposure to society’s negative attitudes, and always having to be an ambassador for breaking down these barriers to a quality life. Ideally, I’d love to just live my life and not discuss blindness or technology, but let my life speak for itself. But since we’re not there yet culturally, disability is still viewed as the worst thing that could happen to a person – even if they’ve been living with it their entire life – so the constant advocacy is necessary to push our rights and status forward.

I’ve been a leader in my community and started public speaking at the age of 10 – once I realized my story was not understood to be the norm for blind people in society, and that my voice might be able to champion lasting social change. Early advocacy efforts centered around fighting for the spread and advancement of Braille in schools for blind students, as only 7% of the nation’s blind know how to read and write Braille, is something that shuts us out from equal education and employment.

I then went through a phase where I needed to see what my life would be like if I did not advocate at all because on top of constantly advocating against systemic oppression, I also have to live in it every single day so I needed to see how much of that I wanted to take on outside of my day-to-day struggles to create a more inclusive world for just me. What rights was I passionate about supporting? How could I turn the injustices I’ve experienced into action that could benefit the discussion around disability as an identity, not just looking at the needs of my population of the disability community? It’s also important to note that one blind person’s experience is one person’s experience; many injustices might be shared, but stories are different, and the way they affect mental health as a result of constant exposure differs from person to person.

Sometimes, the emotional labor of needing to do the work and always being “on” is a lot. There have definitely been times where it has felt very lonely being the only person looking at things from the lens that I am. Not to say I’m the only one doing this work and looking at inclusion from such a broad perspective that includes access to inclusive public schooling, higher education, employment barriers, general societal attitudes that dehumanize over 61,000,000 Americans, but that I sometimes feel like a voice crying out in the wilderness in my direct social circles in my local community. For years, I was the only blind person going through my public school, the only blind student in a very rigid ableist higher education system that is not set up to embrace or empower people to be independent people with disabilities. In many ways, people entering into post-secondary education need to sacrifice themselves and lower their independence just to survive day-to-day. I started to learn about disability rights and justice to learn we have a history and an entire civil rights movement I knew nothing about except for the bare essentials of Rehabilitation Laws and the ADA that govern and somewhat protect my rights.

Coming into contact with this larger disability community gave me a renewed sense of purpose, a new message of inclusion and advocacy, and most importantly helped me to see that I was not alone in the struggles I experienced fighting for my rights to equal education and everyday life experiences, or how inferior society can make a person feel by not truly embracing inclusion and universal design, but placing a dollar value on my livelihood and ability to live an independent life with proper access to equal treatment in public, education, pay and technology that enables me to reach my full potential.

That’s why technology has been amazing. It’s connected me with a community of people, all sharing their positive and negative experiences through various kinds of media – writers, podcasters, filmmakers, photographers, etc. I don’t feel alone in my disability in the way I used to; I’m a part of a very vocal community who share many of the same viewpoints I do around disability’s place in society, and who are committed to fighting for equal rights and significant social change.

Elizabeth Warren’s Plan for Protecting the Rights and Equality of People with Disabilities is the most comprehensive piece of proposed legislation I’ve ever seen come from a politician. We are making noise in the entertainment industry, with real accurate disability representation being shown in the media for the first time ever. Slowly, we are being valued as our own identity, our own community with just as much power in the voting booth and in society at large as any other person. As I said before, anyone can join this club at any time in their lives. Disability does not discriminate against anyone, even though much of the world discriminates against people with disabilities.

Despite issues around data and privacy, big tech companies have done remarkable things for the disability community by offering what used to be hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of technology for free or at a relatively low cost. I’ve seen technology grow in leaps and bounds. When I started out in education, I was doing hard copy Braille on paper – a sighted person’s equivalent to writing with a pencil. Just think of what the ability to type and dictate on a computer has done for the able-bodied world, the transformative effect that has had on society at large, and multiply that by 100,000 – that’s what technology has done for people with disabilities. It has given us a level of freedom never before experienced and allowed us to break every barrier able-bodied people have imposed on us.

Now imagine what we could do if every single university taught accessibility and assistive technology as a part of its computer science/engineering programs. That’s why we continue to see inaccessible content and hardware across the digital space, because it is just not taught, or else the people with the money and power feel it is too costly to implement or will take too long. How would you feel if I told you I wouldn’t be installing any lights or stairs in a building because it would cost too much or take too long? Pretty pathetic argument to make for denying a person their rights if you ask me. But that argument is made every single day by top officials in power and by tech instructors or designers who have an antiquated view of disabled persons as helpless individuals worthy of pity and charity, or people failing to actually engage with the disability community around design of products and websites to make sure the design will work for them and their technologies.

An inclusive world works well for everyone, especially as people age into all kinds of disabilities – the blindness community has a very sizeable elderly population. Build it right from now on, stop attaching dollar signs to inclusive design or making it the last item you do on your development checklist to keep from getting sued, and if we just build the digital and physical world inclusively, we avoid all of the frustrations of not having that inclusion.

A common mistake sighted people make when interacting with blind people is not asking us things. For instance, I’ll be standing on a street corner with my guide dog and people will regularly come up and interact with the dog without consulting me. Or rather, they’ll assume where I want to go. They will grab me and physically drag a visibly and vocally protesting me to wherever they think I’m trying to go. It’s very jarring to be standing on the street and have a stranger reach out and take hold of you without permission. Please don’t assume. Always ask first.

Another misconception people have about disabilities is that it’s a detriment. I think they project their idea of what having a disability would be like onto me. In their minds, it’s a horrifying experience. There have been people for thousands of years who have been blind, deaf, or had cognitive, psychological, or physical disabilities with accommodations who’ve lived capable, independent, happy, and successful lives and are content with who they are as people, despite the world at large refusing to accept this and assuming we are irrevocably broken, lonely sad people in need of religion, medical cures, or charity.

I went through years of training to learn the technology skills, independent living skills, and traveling skills that help me to live my life the way I want to and need to. It’s not like I woke up one day and had everything figured out. People with disabilities are not superheroes or magicians. There is a method to the madness. There’s a community and support, and state-sponsored programs to train people in daily living skills, tech skills, and to prep them for entering education or employment with the requisite social skills needed to secure and keep a job. Where these programs fail is to address by name and help to educate and combat ableism.

Another form of support is having a guide dog. I’m currently on my second guide dog. My first was a yellow Lab named Alpha, who’s still alive. He’s living with my parents on their farm. He had arthritis and got too old to guide so I had to retire him. I was with him for eight years, and now I’m with a black Lab named York.

A guide dog is freedom and security. I know there is a creature on the face of this Earth who loves me unconditionally and depends on me. We’re there for each other and we’re very much a team. When we go walking, if there’s something that comes up like a construction site, we figure it out as a team and we celebrate that success as a team. We’re constantly building each other up in that way. The dog enables me to go literally wherever I want to go while having the confidence that I’m going to be safe. I’m putting my life in his paws and trusting him to guide me around.

He’s also a good judge of people. My dog has a way of letting people he feels are good for me into our circle. He’ll reach out and nibble on somebody’s hand. If he doesn’t like them, he’ll let go immediately. If he likes them, he’ll just chew on their arm. That’s his way of saying, “Hey, you’re good and you can come hang.”

Without a guide dog, my experiences have been very different. There was one time when I was in between dogs. That month really opened my eyes to why I always want to travel with a guide dog. As draining as it can be to always have to remind people not to pet the dog while he’s working, I think people are uncomfortable talking to somebody with a disability. The dog is an easy in for conversations. Most people want to talk about the dog and tell me their dog stories. Without it, I’ve noticed the only time people want to interact with me is if they think I need help. In comparison, when I use a cane, there’s this sense of freedom because a dog is like a child. You have to feed it every day, take it out, and be responsible for it. However, the trade-off is that people don’t approach me in the same way. People, for the most part, leave me alone with a cane, which again can be a very lonely life.

With a guide dog, it’s like having a companion who knows your every move. It’s closer than the bond between me and literally any other creature on this planet, human or animal. He is not a pet, he is my life, my independence, my doorway to so many new experiences and new people. When the knowledge of where we stand in society as a community gets too heavy to hold, when I’m worn out from endless advocacy, he is always there to snuggle and wag his tail and love me on the good days to celebrate our successes and on my darkest nights when I’m not sure how to keep advocating, whether or not it will do any good, or whether or not I know what I’m doing or fighting for. Since we spend 24 hours a day, seven days a week together, we’ve become tied together at a soul level. You know each other’s moves, you know when each other is upset, you can cheer each other up, and you know when each other is happy.

I am very comfortable with my blindness. This is my life. I’ve developed a very keen sense of humanity in the world and looking at it through this lens of blindness. I don’t feel like I’m missing anything. It’s only when structures of power keep people with disabilities from having the tools they need to participate in society that I wish things were different; not that I wish I wasn’t blind, but that the rest of the world wasn’t blind to our struggles and didn’t relegate us to second-class citizen status with a huge mountain to climb to achieve true and lasting equality. But that’s the reason why I fight for inclusion. Because if I didn’t, I would not be where I am today.

Part Three

Inaccessible technology is one of the biggest issues I run into every day, both in my work and life outside of it. It was a huge eye-opening experience for me, learning that I was not able to interact with some apps and websites due to poor coding, rather than the fault of my assistive technology. Assistive technology is like a car and accessibility is like the engine. Your car might run ok, contain the latest and greatest gizmos to help you enjoy navigating from place to place, but without a good engine, it won’t run. It’s the same with regard to accessibility. Without proper programming, where accessibility is put in at the start as opposed to the end of the development process, you won’t be able to do much good with even the most cutting-edge assistive technology. Your site or app needs to have been designed and properly tested. Accessibility is the practice of making sure that your websites, documents, and apps work for all users.

In the same way that the ADA has stipulations around the accessibility of physical places, there are the same stipulations around digital accessibility and design for the digital world. That’s why there are so many lawsuits around accessibility – because it keeps people from being able to access their lives. I could point out a million examples of where technology has opened up the door for people to live much more independent lives, and just as many where that door is locked to us because of poor design and inaccessible content.

Inaccessibility is simply bad code. We see this all the time in universities. Accessibility and assistive technology are not taught in our computer science or engineering classes. People are not taught how to think of these things from a practical, pragmatic standpoint.

If you’re navigating through a website and there’s an image, there’s a way you can add a description to that image. It’s called alt text – or alternative text – and you can describe the image when a blind person using a screen reader scrolls over the image. Alt text adds such depth for blind users, especially with memes and images posted all over social media. Without it, it keeps people in the dark. It’s a matter of equality. It’s a civil rights and human rights issue. Everyone can live their lives the way they want to, but at least give people the option of having a shot at an equitable life by designing things correctly and not leaving accessibility for the very last stage of your design process.

If you build something inclusively so that it’s accessible, it’s going to benefit literally everybody. Everybody’s going to get old or develop some kind of disability at some point. Why not prepare for that now instead of down the road? If we start to change the culture and the thinking around inclusive and universal design, you’re going to mitigate stigma around disability, and the perceived lack of abilities people with all sorts of disabilities face every day. Accessibility won’t erase disability culture, but it will take away a lot of the negative stigma that surrounds disability by showing that it benefits everybody. We, disabled people, are the original problem solvers, because we have literally had to adapt every aspect of our lives to live in a nondisabled world.

Disability doesn’t discriminate based on race, gender, sex, age, etc. Anybody can develop a disability. They say one in four people has a disability, but less than a quarter of that population seeks out accommodations, and a quarter of that quarter is actually receiving the accommodations they need. Less than a quarter of that quarter of that population are actually receiving the assistive technology support for their needs. That’s what keeps me doing what I’m doing. This isn’t easy work because you’re up against a system of power that doesn’t understand the capabilities of people. We’re still having to play catch-up in some ways to all of these other civil rights movements that have gone on.

However, I get to see the benefits of accessibility and when it’s done well. I get to see every day the effect that accessibility has on somebody’s life if you give them the tools they need. I can see them flourish, and be able to develop newer technologies to fit into the gaps in our society. Despite dealing with constant ableism, that’s what keeps me going.

To do my work, I use a screen reader. There are five screen readers that a person could use. There are three on Windows, one for Mac and iOS, and one for Android. I use a program called Aira, which is a visual interpreter service. It pairs the eyesight of a contracted employee with the lens of smart glasses or through the camera on my phone. It gives me a visual description of whatever I’m looking at. I use them to navigate or read things.

There is a near field communication tag company called WayAround. With it, I can fix these tags to clothing. All of the tools in my office are labeled with them. You can write a label on this tag and then read it with your phone. So when I’m home at night and I’m cooking, I know that I can differentiate the cumin from the garlic powder. I can scan one of these tags in about two seconds, as opposed to Braille. Braille labels also tend to flake off pretty easily.

I also use Google and Alexa as smart home assistants to be in control of my house. I say, “good morning, Google” or “good morning, Alexa”, and I use them both for different things. Either one of them can brew my coffee, turn the lights on, unlock the door, tell me the weather or traffic, and check my calendar for events with one single command.

I grew up on a farm and I remember the days before all of this technology hit everybody’s lives. It’s brought me freedom, independence, confidence, and self-assuredness.

Audio description, in particular, has come a long way. When I first discovered audio description as a kid, the first show that I ever saw that was described was the kids TV show, Arthur. You could only get it at certain times. It was one or two of the shows that were described. Then they started putting that onto VHS tapes and you would have to rent them with audio description from a library for the blind. They had to have enough copies in stock of that particular movie for you to be able to get it. Now, I can pull out my phone and pull audio description up on Netflix, Amazon, or Apple TV.

I’ve watched many movies without audio description. For me, it just adds more work because then I have to go back and look at Wikipedia and read through the plot summary. If it’s a movie I’m really dedicated to knowing what’s going on, I will find a copy of the script and literally go scene-by-scene to fill in the visual details that I’m missing. But because there’s audio description, I don’t have to do that. My partner and I can sit down at night and watch a movie. She gets her visuals and I get my audio description. I can even pipe the audio description track into my headphones so that I’m the only one that hears it in certain apps. Going to the movies is pleasurable again, as I can do that in the theater too so I’m the only person hearing the description.

Aside from the work I do, I make music, write, and connect with people. I’m finishing up an album right now that’ll be out within a few months! It’s called Comin Up From the Mud, my first time with a full band. I will be touring on weekends in support of it. I’m also a podcaster, with a background in radio production. Audio is my favorite medium to connect with people.

I also love to read and cook. When it’s not frigidly cold, I love nature. I’ll go for a nice hike or swim with my dog, York.

Since much of my life is centered around technology, I try to give myself one day a week where I use as little technology as much as possible. Usually, that’s a Saturday or Sunday. During one of these days, I get housework done, cook, or just binge-listen to podcasts or -read something. I appreciate moments of quiet and spending time with good people.

There is a lot of complexity to my work in the disability community because I’m trying to change societal perceptions, fund new technological ventures, ensure people get the tools they need, and analyze the world and how disability’s place in it is changing. That’s a lot of noise in my head, and so when I have the freedom to be home and still, I love a simple life where I can use technologies to help me meet the full potential I know I’m capable of.

After all, that’s why they were built.

Faces Behind the Screen would like to thank Joshua Pearson for participating in our storytelling project. If you’re interested in sharing your story with us, fill out our nomination form.

Faces Behind the Screen is a storytelling project focusing on members of the Deaf and hard of hearing community.