Australian Web Accessibility & Closed Captioning Rules

Updated: June 3, 2019

Approximately 1 in 6 people in Australia are deaf or hard of hearing. For those Australians, closed captions are needed to provide equivalent access to television, films, and web video.

The US and UK have disability laws in place that require closed captioning for broadcast media, government resources, and even education. What are Australia’s closed captioning rules?

Read on for a summary of web accessibility trends and closed captioning rules in Australia, or download our white paper on web accessibility and captioning in New Zealand & Australia.

Broadcasting Services Act

Australian broadcasters have been compelled to add closed captioning to programming since the 1992 Broadcasting Services Act. This law gave Parliament the right to establish codes of practice that include captioning of programs for the hearing impaired. In 1999, the BSA’s title was amended with “(Online Services)” to cover digital television in addition to radio broadcasting.

Additional amendments passed in 2001 and 2010 adjusted the requirements for how many public television programs, or “Free Air TV,” needed captions and established timeframes for compliance.

| Time Period | Percentage of programs needing closed captions | Daily Hours of Broadcast | Type of Programming |

|---|---|---|---|

|

-1992 |

N/A |

N/A |

No regulation until BSA passes |

|

2001-2011 |

100% |

4 hours |

All news & current affairs TV programming.

All programs aired between 6pm-10pm |

|

2011-2012 |

85% |

18 hours |

All programs aired between 6am-12am

All news & current affairs TV programming. |

|

2012-2013 |

90% |

18 hours |

All programs aired between 6am-12am

All news & current affairs TV programming. |

|

2013-2014 |

95% |

18 hours |

All programs aired between 6am-12am

All news & current affairs TV programming. |

|

July 1, 2014-present |

100% |

18 hours |

All programs aired between 6am-12am

All news & current affairs TV programming. |

Exemptions

Some Australian television content is exempt from closed captioning requirements. Exemptions include:

- Non-English programs

- Non-vocal, music-only programs

- Incidental or background music lyrics

- Unscheduled live sports programs

- Extended new coverage

- Community broadcasters

Multichannel Rule

If a program aired on its parent channel with captions, it must air on other channels with closed captions as well.

Australian Closed Captioning Quality Standards

Comparable to the FCC in the United States, the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) creates and enforces broadcasting standards for the country’s Free Air TV. The BSA grants the ACMA power to set quality standards for closed captioning as well.

Industry Guidelines on Captioning Television Programs

The ACMA released the “Industry Guidelines on Captioning Television Programs,” a non-legally binding report on captioning best practices for grammar, punctuation, placement, timing, and formatting. A few noteworthy recommendations include:

- Use font color to delineate different speakers or sound effects.

- Children’s programming should have a slower caption speed to match their reading level.

- Captions should be in sentence case, not ALL CAPS.

Section 1.23 of the Commercial Television Industry Code of Practice

The ACMA issued the Commercial Television Industry Code of Practice, with which all licensed Australian broadcasters must comply. Every year, licensees must submit an annual report with proof of compliance to the ACMA.

Section 1.23 of the code relates to closed captioning. It requires that all licensed Aussi broadcasters:

1.23.1 ensure that closed-captioning is clearly indicated in station program guides, in press advertising, in program promotions and at the start of the program;

1.23.2 exercise due care in broadcasting closed captioning, and ensure that there are adequate procedures for monitoring closed captioning transmissions;

1.23.3 provide adequate advice to hearing-impaired viewers if scheduled closed captioning cannot be transmitted. If technical problems prevent this advice from being provided in closed captioned form, it must be open captioned as soon as reasonably practicable;

1.23.4 when broadcasting emergency, disaster or safety announcements, provide the essential information visually, whenever practicable. This should include relevant contact numbers for further information.

Subscription TV Captioning Rules

A 2012 amendment to the BSA added regulations for captioning subscription television. Subscription channels were divided into categories based on their content, which would dictate the amount of closed captioning needed.

The general requirements for captioned programming on subscription TV are:

Movie Channels

- The first 6 movie channels must caption up to 80% by 1 July 2015

- The next one must caption up to 60% by 1 July 2015

- The remainder must caption up to 50% by 1 July 2015

General Entertainment

- The first 18 general entertainment channels must caption up to 60% by 1 July 2015

- The next 16 general entertainment channels must caption up to 50% by 1 July 2015

- The remainder must caption up to 30% by 1 July 2015

News

- News channels must caption up to 20% by 1 July 2015

Sports

- Sports channels must caption up to 20% by 1 July 2015

Music

- Music channels must caption up to 10% by 1 July 2015

The subscription television caption requirements are measured against a 24-hour period whereas the free-to-air requirements are against an 18-hour period.

NOTE: quotas increase by 5 percentage points per year.

Other Australian Broadcasting Closed Caption Rules

DVDs

Australian DVDs and Blu-ray disks are not currently subject to closed captioning regulations, except for those films financed by Screen Australia after July 1, 2011, which must include closed captions and audio descriptions. The Australian Home Entertainment Distributors Association accepts complaints about DVD accessibility.

Video on Demand (VOD)

In April 2015, Media Access Australia launched Access on Demand, a comprehensive report on the accessibility of Australian video on demand. The report encouraged Australian broadcasters to caption all archival TV programming by the end of 2015, and all VOD programming by the end of 2016. Citing US & UK captioning law as a standard, Access on Demand concludes with a call to action for the federal government to pass more explicit closed captioning laws if broadcasters don’t caption voluntarily.

Disability Discrimination Act of 1992

Australian accessibility law expanded beyond broadcast with the passage of the 1992 Disability Discrimination Act (DDA). Nearly all Australian states and territories had their own antidiscrimination legislation in the 1980s; the DDA was meant to standardize the laws and consolidate their enforcement federally.

Comparable to the Americans with Disabilities Act in the US or the Equality Act in Great Britain, the DDA protects the civil rights of individuals with disabilities and mandates certain accommodations for them. Violations of the DDA are considered discrimination, and infractions are reported to the Australian Human Rights Commission.

Section 24

Section 24 of the DDA calls for accessibility of all goods, services, or facilities for people with disabilities. Part A of Section 24 reads:

It is unlawful for a person who, whether for payment or not, provides goods or services, or makes facilities available, to discriminate against another person on the ground of the other person’s disability:

1. by refusing to provide the other person with those goods or services or to make those facilities available to the other person;

That language can be interpreted as requiring web accessibility accommodations–the absence of which would deny disabled people access to information and constitute a breach of their civil rights. However, without explicit references, it would be difficult to compel Australian organizations to make their web and video content accessible on the basis of this section alone. A discrimination lawsuit would be needed to clarify the DDA’s application to digital access. The case of Maquire v. Socog was a major step in this direction.

Maguire v. SOCOG

Section 24 of the DDA was cited in a landmark web accessibility case in 2000, Bruce Lindsay Maguire v. Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games.

Bruce Lindsay Maguire, blind since birth, filed suit against SOCOG for failing to make their website accessible to the blind. He demanded alt text on images and changes to the site navigation so that he could browse the content with his braille reader. He argued that failure to accommodate him was a violation of the DDA.

SOCAG initially resisted, claiming that they were not intentionally discriminating against the blind and that the cost of making those changes would cause “unjustifiable hardship.” The court disagreed. SOCAG was ordered to make the requested updates to their website and compensate the plaintiff $20,000 AUD for damages.

This set a bold precedent that any Australian website created for use by members of the public must be accessible to everyone regardless of their sensory abilities. In response, the Australian government developed a plan for embracing inclusive web design.

National Transition Strategy

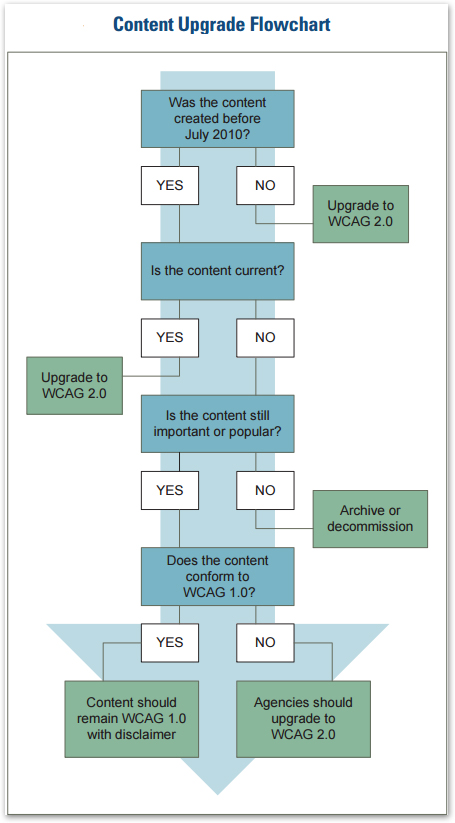

What is the NTS?

The plan was called the National Transition Strategy (NTS), and it was meant to make government web content accessible to people with disabilities. It was released along with an official statement of endorsement for WCAG 2.0 accessibility standards.

The Web Accessibility National Transition Strategy sets a course for improved web services, paving the way for a more accessible and usable web environment that will more fully engage with, and allow participation from, all people within our society.

— Australian Department of Finance

The timeframe for compliance was:

- All websites ending in .gov.au must be WCAG 2.0 level A compliant by the end of 2012

- All websites ending in .gov.au must be WCAG 2.0 level AA compliant by the end of 2014

Level A compliance requires that all pre-recorded video be captioned and transcripts be made available for audio-only files.

Level AA compliance includes those requirements, plus live captioning of live-streaming video.

The NTS guidelines were adopted by many Australian states, territories, and municipalities, with some modifications. For example, Queensland decided to implement all of WCAG 2.0 except for some of the more challenging accommodations, while Western Australia delayed their compliance by one year. Local governments also differ on whether or not Level AA is mandatory. All Aussi state governments – except for South Australia – have agreed to meet WCAG 2.0 level A standards, which require closed captioning on all pre-recorded video.

NTS aimed to make all federal websites WCAG 2.0 AA compliant by 2015, but that turned out to be overly ambitious.

Compliance Challenges

Although the federal government has made a lot of positive headway, it has fallen short of its deadlines for WCAG compliance as set forth by the NTS. By the end of 2012, only 26% of government websites were Level A complaint. In 2015, many government websites in Australia are still behind schedule.

Why has inclusive design been so difficult to implement? Five reasons cited by Aussi web accessibility expert Dr. Scott Hollier are:

- Accessibility specialists are isolated from other departments, so there’s a lack of organization-wide buy-in.

- Outdated technology and legacy systems.

- An unproductive blame game between web developers and content producers about who is responsible for preserving accessible design.

- Not enough time to meet compliance deadlines with available resources.

- Lack of accessibility auditors to measure compliance.

Despite these shortcomings, there is hope for progress. Dr. Hollier writes, “the enthusiasm and desire from ICT professionals to work on accessibility issues…has never been stronger.” The more attention and resources devoted to the cause of accessible web design, the sooner the NTS goals will be realized.

Digital Transformation Office & Digital Service Standard

The Australian government formed a new department to continue the work of the NTS after it ended: the Digital Transformation Office (DTO).

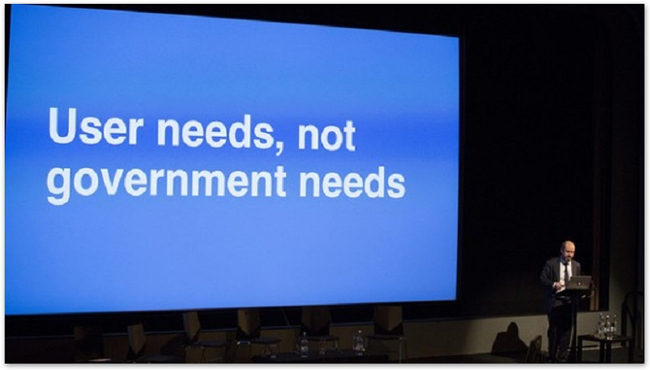

The DTO sets a nationwide Digital Service Standard (DSS), which “establishes the criteria that Australian Government digital services must meet to ensure our services are simpler, faster and easier to use.”

While the DSS is not as technical as the NTS when it comes to accessibility requirements, it stresses the need for optimal UX on the web.

Part of the DSS is a 16-point design standard that emphasizes usability. The 3 criteria that address web accessibility are:

- Criterion 8—”Build the service with common look, feel, tone and function that meets the needs of users.” For content to meet the needs to deaf or hard of hearing users, that means adding transcripts for audio and captions for video.

- Criterion 10— “Test the service on all common browsers and devices, using dummy accounts and selecting representative samples of users.” This calls for universal accessibility testing of online goods and services.

- Criterion 16—”Provide ongoing assurance, supported by analytics, that the service is simple and intuitive enough that users succeed first time unaided.” Accessibility must keep up with new features and redesigns.

Web Accessibility & Captioning in Australian Education

In his article on a post-NTS Australia, Dr. Hollier writes:

Since the NTS started, Hollier noticed a significant increase in demand for web accessibility training for educators. Steadily, more .edu.au websites are adopting WCAG principles, including adding closed captions to web video. Accessibility advocates are rallying for more comprehensive captioning in Australian schools, pointing to research studies for proof of their benefits.

Statistics on Australian Students Who Would Benefit from Captioned Video

Cap That! is a national awareness campaign that promotes:

Cap That! assembled statistics on the total number of students who would stand to benefit from captioned video. In total, over 1.4 million students – or 31% of Australian students 15 or under – would benefit from captions.

| Total school students in Australia | 4.5 million | |

|---|---|---|

| Total students with ASD, ADHD, LD |

800,000 |

18% |

| Total Deaf or hard of hearing students |

12,000 |

0.3% |

| Total ESL students |

600,000 |

13% |

| Total students to benefit directly from captioned video |

1,412,000 |

31% |

University of Western Australia Study

A University of Western Australia study surveyed 130 students with physical, sensory, learning, or cognitive disabilities. Of that pool, 66% considered captioned lecture recordings “essential” for their education.

These findings motivate Australian educators to adopt more multimedia transcription and captioning practices in the future.

Further Reading

Subscribe to the Blog Digest

Sign up to receive our blog digest and other information on this topic. You can unsubscribe anytime.

By subscribing you agree to our privacy policy.